Jersey City: The Quiet Stories of History

Recently, a local historian and lifelong Jersey City resident shared with me his joyous surprise upon discovering a cache of newspaper articles concerning a prominent late-nineteenth-century resident of his neighborhood and this resident’s failed attempt to sell his private park to the Jersey City government. This nineteenth-century gentleman was Bernard Vetterlain.

Bernard Vetterlain earned his fortune in tobacco sales and lived near today’s Summit Avenue and Astor Place in Jersey City until 1870. In addition to a grand home and estate, Vetterlain owned a private park in the neighborhood. That’s right, a private park. Reportedly, this park was a beautiful, soothing sanctuary with gravel paths, flower gardens, well-placed benches, and a Japanese waterfall. This was Jersey City’s Gramercy Park.

Shortly after municipal consolidation formed Jersey City in 1870, Vetterlain offered to sell the newly organized city government his park for a purportedly fair price. After much haggling and discussion, the city ultimately declined. After Vetterlain’s death, developers purchased his Jersey City property from his heirs and unceremoniously chopped up the land into multiple lots for home building. Vetterlain’s park was lost. A single watercolor by an obscure Hudson County artist, August Will, stands as the only pictorial evidence of the park. (For the record, I have not seen this painting.)

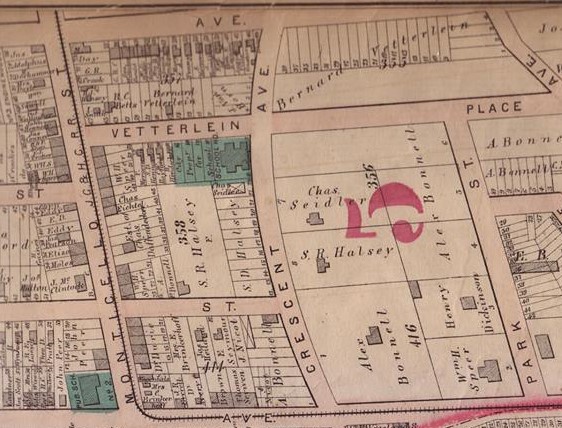

Map of today’s Astor Place neighborhood, circa 1870. Vetterlain Place is now Astor Place. Notice the name Bernard Vetterlain attached to multiple properties.

Vetterlain’s heirs could have preserved the park or the developers could have viewed it as an amenity to attract home-buyers. Unfortunately, the temptation of easy profits proved to be too great, and this treasure was lost.

The story of Bernard Vetterlain and his ill-fated park fascinated me. Who was Vetterlain? What would a stroll through his private grounds be like? Would one hear birds and insects? Would one smell blooming flowers and damp earth? If that park had been saved, what would it look like today? What would the surrounding neighborhood, Astor Place, look like? What possibilities died with the felling of the first tree in Vetterlain’s Park?

Bernard Vetterlain, 1819-1892 (Courtesy of Findagrave.com).

As I considered this vanished place, I gradually realized that the story of Bernard Vetterlain distilled not just the importance of Jersey City’s history, but of local history.

Much like people, many places lead quiet lives (that doesn’t imply that they lack drama, loss, and surprise). The past of most places did not shatter the world or change it in convulsive ways. However, that doesn’t mean that local history should be forgotten and that it doesn’t deserve to be collected. Local history–its figures and stories–imbue a place with color and character. Local histories overflow with small, quiet stories, like that of Vetterlain’s park.

Jersey City holds a library of these quiet stories. Unfortunately, Jersey City seems to care little for the flourishes of its local history. Brooklyn, New York–to name one locale–has mined its history to fashion a seductive image of itself as an urban pastoral. Clearly, this cultural project has proven to be profitable to property owners and real estate interests, but it has nurtured Brooklyn into the grassroots epicenter of music, art, literature, food, and culture in the New York metropolitan region, if not the United States.

Beyond engendering an aesthetic and a savvy business plan, why might such devotion to local history matter? When people take pride in their neighborhoods, they become involved in them. They become active in local organizations, work toward improving schools, open small businesses, and ultimately choose to stay in a neighborhood or city. An appreciation of local history generates genuine pride and contributes to a sense of community. History can make a town or city a very nice place to call home.

Although he never invented a notable gadget or penned a famous book, Bernard Vetterlain and his private park matter to Jersey City. They provide it with a dash of color and flair. Wherever you may live, search for your own Bernard Vetterlain. I doubt that you’ll be disappointed upon finding him.