The Empty Chair

This past spring, I traveled to London for the very first time. I approached the trip not as a getaway or a vacation but as a pilgrimage to the epicenter of the English-speaking world. For a writer and a humanist such as myself, London represents literature, art, history, architecture, and learning—the foundation of my creative and intellectual identities. So, yes, I was beyond excited to be exploring the streets and sites of foggy London Town.

As a compulsive reader since a very young age, my images and mapping of the city rested on stories and books. One writer who exerted an oversized impact on my conception of London and British life overall was the titan of Victorian novelists, Charles Dickens. A stop at the museum dedicated to the author in a former home of his stood at the top of my itinerary.

Expecting a relatively sedate and empty institution, I was pleasantly surprised to find the Charles Dickens Museum bustling with readers. While admiring one period room—a recreation of the author’s personal library and study—another visitor and I shared our favorite Dickens’s works and discussed our first respective encounters with his writings as if exchanging memories of an old, mutual friend.

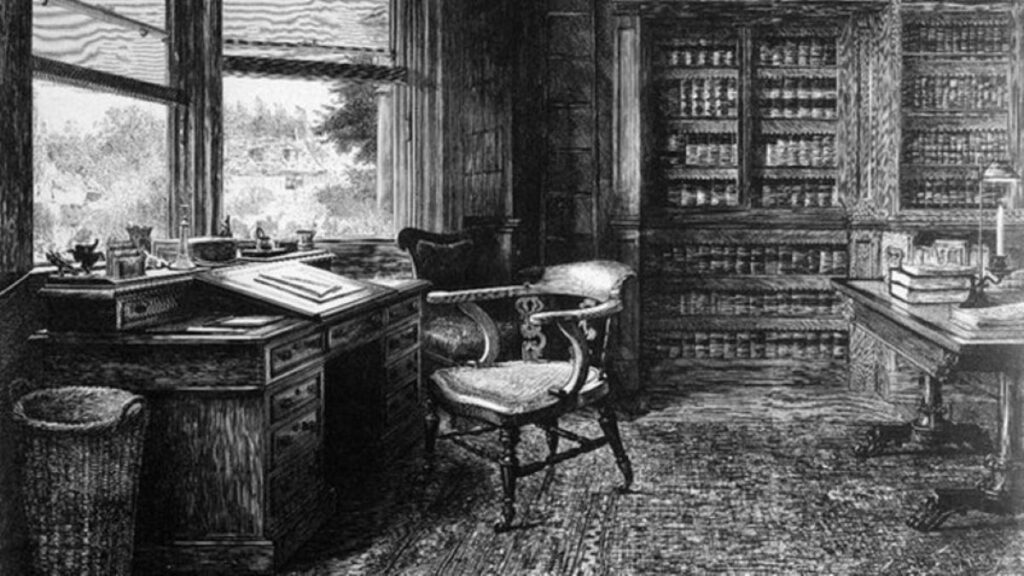

A specific piece displayed in the museum haunted me long after my tour. This was The Empty Chair, Gad’s Hill–Ninth of June 1870, a print of an engraving by Samuel Luke Fildes, a painter, illustrator, and collaborator with Dickens on his unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. (The Free Library of Philadelphia holds the painting upon which the engraving is based.) The work depicts the interior of Dickens’s study. Its walls are lined with full bookshelves; an Oriental rug covers its hardwood floor. Looking toward a bay window with a garden view rests a desk holding writerly bric-a-brac and an unfinished manuscript. In front of the desk sits an empty chair representing the death of Dickens and the grief experienced by his contemporary reading public. Today, the Charles Dickens Museums owns both the desk and chair featured in Fildes’s work.

Yet, The Empty Chair offers more than a somber reflection on the passing of a beloved literary icon. Throughout our lives, we shall experience our own private empty chair many, many times over. Following the loss of a parent, a spouse, a sibling, a friend, or even a child, we might gaze at a spot favored by those gone and feel pain anew. Such a space, both a void and a remembrance, will never be filled. Such a loss will never be forgotten. However, Fildes’s print and other explorations of mourning and heartache provide us with comfort and understanding. They remind us that we are not alone in our confusion and suffering. Much like philosophy or scripture, they assure us that joy and sadness and life and death are inextricably intertwined, essential and conjoined components of the human condition.

Although the British world captured by Dickens largely no longer exists, readers still discover relevancy, connection, and power in his words, characters, and novels. The Empty Chair exerts a similar hold, whispering to us of what awaits us and speculating on what might come after.