Statues for Whom?

Statues stand as markers or symbols of how we publicly view history. They sit in our parks and and in front of our public buildings. Before the protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd, few of us likely paid much attention to them as we walked to work, returned a library book, or reported for jury duty.

However, we’re now looking at our public monuments and asking what they might represent and how we wish to tell our history. Local officials and organizations have removed long-controversial figures, such as the American Museum of Natural History’s President Theodore Roosevelt monument or Philadelphia’s statue of former Mayor Frank Rizzo.

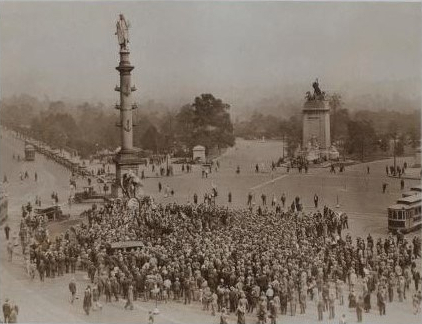

“Manhattan: Columbus Circle – Celebrations – Tribute to Columbus,” 1933. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Unfortunately, protesters have targeted statues with increasingly less discrimination. A monument to Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, was vandalized in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Cervantes himself was enslaved for five years. In Madison, Wisconsin, a crowd toppled a memorial to abolitionist Hans Christian Heg. He died serving the Union Army in the Civil War.

All the above instances represent relative simple decisions (Rizzo told citizens to “vote white.”) or wanton acts of vandalism. But how to decide upon a statue holding conflicting meanings or when its historical interpretation remains unsettled in the public imagination?

Statues of Christopher Columbus can be found in neighborhoods and cities throughout the United States. Some were erected to commemorate the four-hundredth (and even five-hundredth) anniversary of Columbus landing in the Americas. Others were commissioned by or for Italian-American communities to celebrate their newfound place in American society. Many statues falling in the latter category sit in numerous New Jersey cities.

Christopher Columbus memorial formerly in the North Ward, Newark, New Jersey. (Courtesy of Newarkology!)

For generations, Newark’s North Ward was an Italian stronghold. In 1972, a Christopher Columbus statue was dedicated on Bloomfield Avenue in front of St. Francis Xavier Church. Local Italian-Americans raised the funds for the memorial. Assimilation and white flight led to an exodus of Newark’s Italian community for the suburbs and the Jersey Shore. Today, the area is largely Hispanic.

On June 26, 2020, this Christopher Columbus statue was removed from its pedestal with a crane and driven away on a flatbed truck. According to news reports and the city government, the action was taken by private citizens. Legality and propriety of the removal aside, did the Columbus statue still hold meaning or value for North Newark? The Italian community–its original sponsor and public–has long since departed.

What should be done with a public statue–especially a controversial one–when the community it represented no longer exists? This might be the next question to roil the ongoing debate over public monuments.