An Afternoon in Greenwich Village: Fading Bohemia

Several weeks ago, I spent a Friday afternoon in Greenwich Village in Manhattan. Any casual devotee of the arts and literature understands the prominent position of Greenwich Village in the constellation of American bohemian. Authors, poets, playwrights, actors, and musicians began gravitating to the neighborhood before the Civil War with the opening of the Tenth Street Studio Building in 1857, the first structure designed for practicing artists in America. This pilgrimage lasted well into the 1960s.

Today, struggling artists, brooding writers, and ragtag songsters no longer look to Greenwich Village as their mecca (I’m unsure if they even look to New York anymore). Only the artists fortunate enough to have locked down a rent-controlled or rent-stabilized apartment decades ago now call the neighborhood home. The only visible “artists” seen walking the streets are television and movie actors, models, and music moguls. Greenwich Village is the home of the creative-class’s one-percent. This population’s lasting impact on culture might prove to be negligible. The world is too much with them.

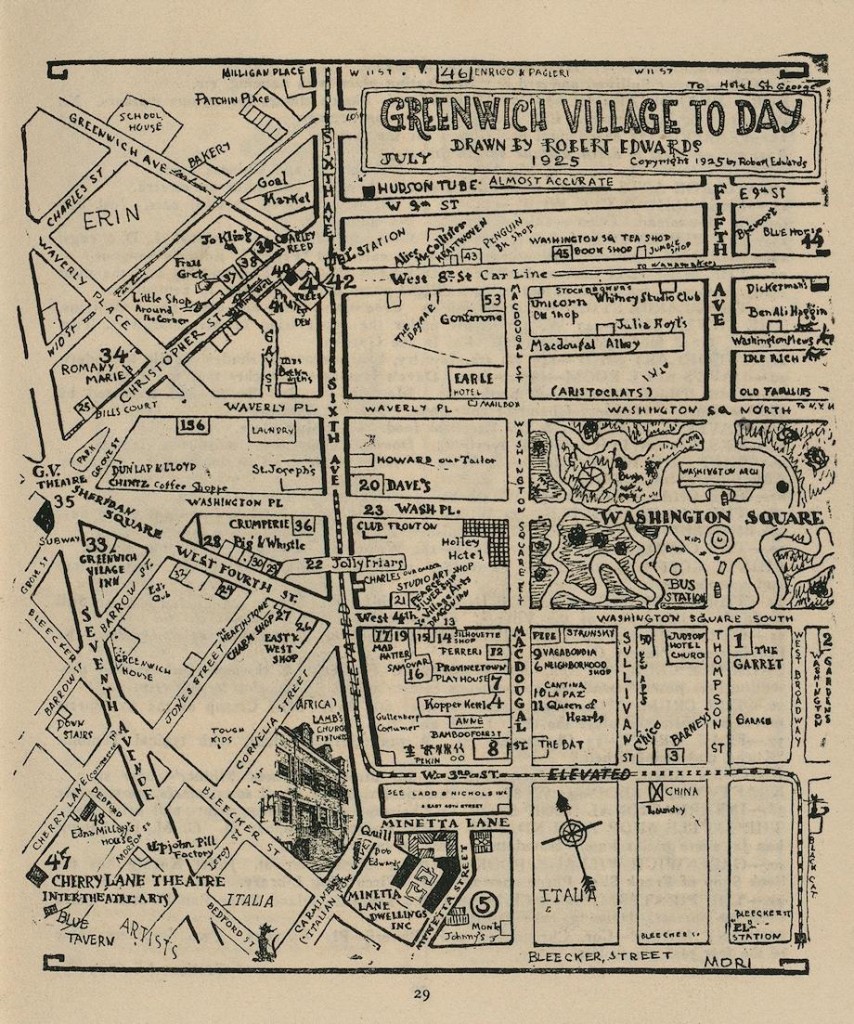

Map of Greenwich Village from the Greenwich Village Quill, 1925 (Courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin).

Those saddening realities aside, I enjoyed my stroll through the Village. Since the day was young, tourists had yet to clog the streets, searching for a shadow of this past bohemia (wasn’t I doing the same thing?). I purchased a tin of tea at McNulty’s Tea & Coffee with its burlap sacks of fragrant coffee beans on the floor and antique measuring scales. At bookbook, I found a cheap biography of Frederich Law Olmsted, the mastermind behind many great parks throughout America, including Central Park and Prospect Park. Later, I watched a French film at the Film Forum, a temple to cinema, where no one checks his or her cell phone and destroys the momentary dream of movie-going. I finished my afternoon with a sandwich and an iced coffee at Grey Dog, an off-beat cafe in the classic sense. All those businesses carried a whiff of the neighborhood’s fading wonder and grandeur. My afternoon resembled an archaeological expedition searching for remainders of the legendary tribe of bohemians.

Those blocks and streets used to hold many more bookstores, record shops, and quirky, one-of-a-kind businesses. For example, the departed Aphrodisia specialized in dried herbs and spices on Bleecker Street. When passing by, I would pop into that store to play with its two resident cats. Such spaces are increasingly endangered. Once they close, they will never return. Such spaces make Greenwich Village and any city neighborhood interesting and vital. Although needed for daily living, chain drugstores and bank branches do not make a block or a neighborhood worth caring about and fighting for.

Manhattan is no longer a place for artists or really any individual with limited means. It now belongs to financiers and foreign oligarchs. Still, Manhattan contains interesting buildings and streets; soothing, elegant parks; and a wealth of dining, entertainment, and cultural fare. Artists, writers, and their brethren can still enjoy Manhattan, as I did during my afternoon in Greenwich Village, but they cannot afford to live there. We are mere visitors.

In this aspect, does not Manhattan resemble Paris and other past hotbeds of creativity? What does this mean for the arts and letters? What does this mean for the future relevance of New York City?