The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: a Review

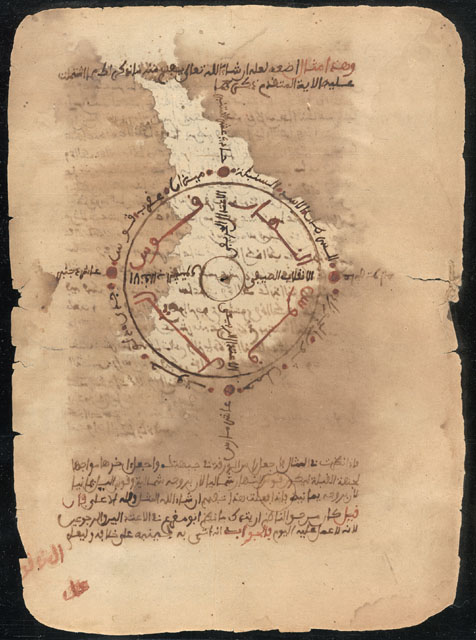

Timbuktu, a city in arid northern Mali, once stood as a great center of learning, culture, and scholarship. From the 13th century to the 17th century, Timbuktu attracted students, writers, poets, scientists, and theologians from across the Islamic world. Manuscripts were collected in the city and were treasured possessions passed down in families across generations and centuries. These manuscripts explored every imaginable topic including astronomy, medicine, jurisprudence, and romantic poetry. Most of this literature was written in ornate Arabic script but also in the local and regional African dialects and languages.

Joshua Hammer, a veteran journalist, beautifully describes this Timbuktu and its culture, the attempts to develop the city into a contemporary center of learning, and then the city’s violent assault by Islamic forces in The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu. Admittedly, the title sounds juvenile and will surely become dated in a few years, but I imagine that an editor or a marketing executive imposed the title on Hammer’s book. Title choices aside, Hammer constructs a wonderful narrative and builds a great sense of drama. This is non-fiction writing at its best.

In the 1980s, Abdel Kader Haidara inherited his father’s manuscript collection and was recruited by the Ahmed Baba Institute to scour the city and countryside and to visit tribal villages and desert oases in an attempt to secure the vast manuscript patrimony of Timbuktu. Although protected by the dry climate of northern Mali, every manuscript was threatened by termites, dirt, dust, mold, and merciless time. Haidara began to see his life’s mission as collecting and preserving the intellectual heritage of Timbuktu.

Manuscript (Courtesy of Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library, Timbuktu)

Haidara and his fellow librarians within and without Timbuktu saw the manuscripts as demonstrating that Africa held a rich, written cultural legacy prior to European colonialism and that Islam, as a religion and culture, contributed to the art and thinking of the larger world. Simply put, the people of Timbuktu, Africa, and the Islamic world were not barbarians and savages.

Haidara’s project moved forward with great success, attracting funding and technical support from Gulf nations, Europe, and the United States. Prominent American scholars and intellectuals were drawn to Haidara’s work because it revealed a wondrous, proud African culture. Henry Louis Gates traveled to Timbuktu and filmed a documentary on the manuscripts and their libraries. Gates claimed that his visit “was one of the most moving days of [his] life.” He became “emotional, holding th[o]se books in [his] hands.”

Then, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) stormed through northern Mali, easily routing the Malian military and seizing control of Timbuktu in 2012. Haidara immediately realized that the manuscripts were in real danger. Thinking little of his own safety, Haidara first systematically removed the manuscripts from the libraries and collections throughout city and hid them with trusted colleagues, friends, and family members. No one rejected his requests. Then, he organized a smuggling ring to ship the manuscripts out of Timbuktu and into the national capital in southern Mali.

Abdel Kader Haidara sorting through manuscripts smuggled out of Timbuktu (Courtesy of National Geographic).

Aside from being a compelling read and a love-letter to books (albeit in manuscript form), The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu comments on very real and very dangerous phenomenon in our contemporary world.

Two very distinct interpretations and visions of Islam are vying for dominance. The historic Islam of Timbuktu captured in its manuscripts and traditions argues that Islam and Islamic culture are fully compatible with modernity, intellectualism, and coexistence with different cultures and religions. Presumably, most practitioners of Islam and residents of Muslim nations would agree that they hold this viewpoint. The other pole is unfortunately all-too-familiar: Al Qaeda, Boko Haram, ISIS, and other jihadists. These groups and their supporters espouse a much darker and more violent interpretation of Islam and exhibit no hesitation in imposing it upon others and maiming or murdering those who disagree.

One constant feature of this ugly imagining of Islam is a hatred for human culture. ISIS has destroyed antiquities and invaluable religious and archaeological sites throughout Iraq and Syria. They destroyed Mesopotamian, Christian, Roman, Shiite, and Sunni artifacts and sites. They proudly posted video of their followers destroying the tomb of the prophet Jonah in Nineveh.

Human culture–for example, paintings, literature, houses of worship, and ruins–do not belong to a specific people, nation, or religion. Culture belongs to all humanity. It educates us, inspires us, and enriches us. It helps us understand one another as individuals, religions, and countries. It shows us the wonder, beauty, possibility, and truth of the world. This is why it threatens jihadists. Abdel Kader Haidara understood this and he strove to save the culture of Timbuktu. Joshua Hammer understands this and presents The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu as a warning.

In early 2013, French and pan-African military units drove AQIM from Timbuktu and northern Mali. Before fleeing Timbuktu, the jihadist forces burnt any manuscript which they could find.