My Introduction to Permaculture

This past week, I attended a lecture on permaculture by Andrew Faust at the Brooklyn Brainery. Before I write about permaculture, indulge me as I describe the Brooklyn Brainery.

The Brainery is a fascinating place. Most nights, and sometimes twice per night, the Brainery offers classes and lectures for a low cost. The subjects range from the erudite to the outright obscure. Interested in home-brewing? There might be a class. Interested in contemporary Australian parliamentary politics? There might be a class. Interested in iconic perfume bottles? There might be class.

(Courtesy of Brooklyn Brainery)

At first blush, the Brainery seems to offer the over-educated, creative denizens of New York something new and quirky; however, the model is old and tested. Lectures were a popular mainstay of intellectual and public life of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most notably the Chautauqua movement. Aspiring citizens from all educational and economic segments of society attended such events to expand their minds, build an understanding of the arts, and learn about the world beyond their own tiny corners of America. Education and cultural enrichment were valued. A grasp of current affairs, scientific discoveries, and literature stood as a sign that one seriously embraced his (or her) role as a responsible, respectable citizen of the republic. How much our society has changed.

As an avid gardener and a self-declared urban homesteader, I’m always searching for methods to minimize my food miles and my carbon footprint. When I saw the listing for the permaculture class, I signed up.

So, what’s permaculture?

Permaculture is both an agricultural method and an approach to life. Practically speaking, its techniques and philosophy stem from East Asia (China, Japan, and Korea). Permaculture observes the local environment and follows its patterns: it does not attempt to “tame” nature, contrary to Western farming practices. It avoids pesticides, fertilizers, heavy machines, and other features of industrial agriculture. Permaculture also strives to build a system with zero waste. For example, the waste from food production is returned to the soil in the form of compost.

Andrew Faust presented permaculture as a series of choices. One can choose to perform actions and to lead a life that improves the earth’s water, air, plants, and wildlife. One can choose to support and to develop a food production system that nourishes individuals, families, and communities. One can choose to attempt to positively impact nature and the human race.

Or one can choose otherwise.

Faust’s message was positive and empowering. Instead of waiting for faceless corporate entities or sclerotic governing institutions to reform and to initiate top-down change, we–individually and collectively–can begin working to construct a better world. This is a drastic improvement from mainstream environmental thought, which seems to ask little of the individual. Why should you or I have to change? We are not the problem. Someone else is. Someone far, far away.

Skeptics will scoff: sorry, this can’t be done. The industrial-agriculture complex will always remain with us. Maybe. But why not try something else? Faust introduced the audience to three very different cities that are embracing elements of permaculture: Shanghai, Berlin, and Paris. Shanghai, a city of over 25 million–yes, 25 million—grows and harvests somewhere between 55% and 66% of its produce within the city. Keep in mind, Shanghai is denser, dirtier, busier, and more populated than any Western metropolis.

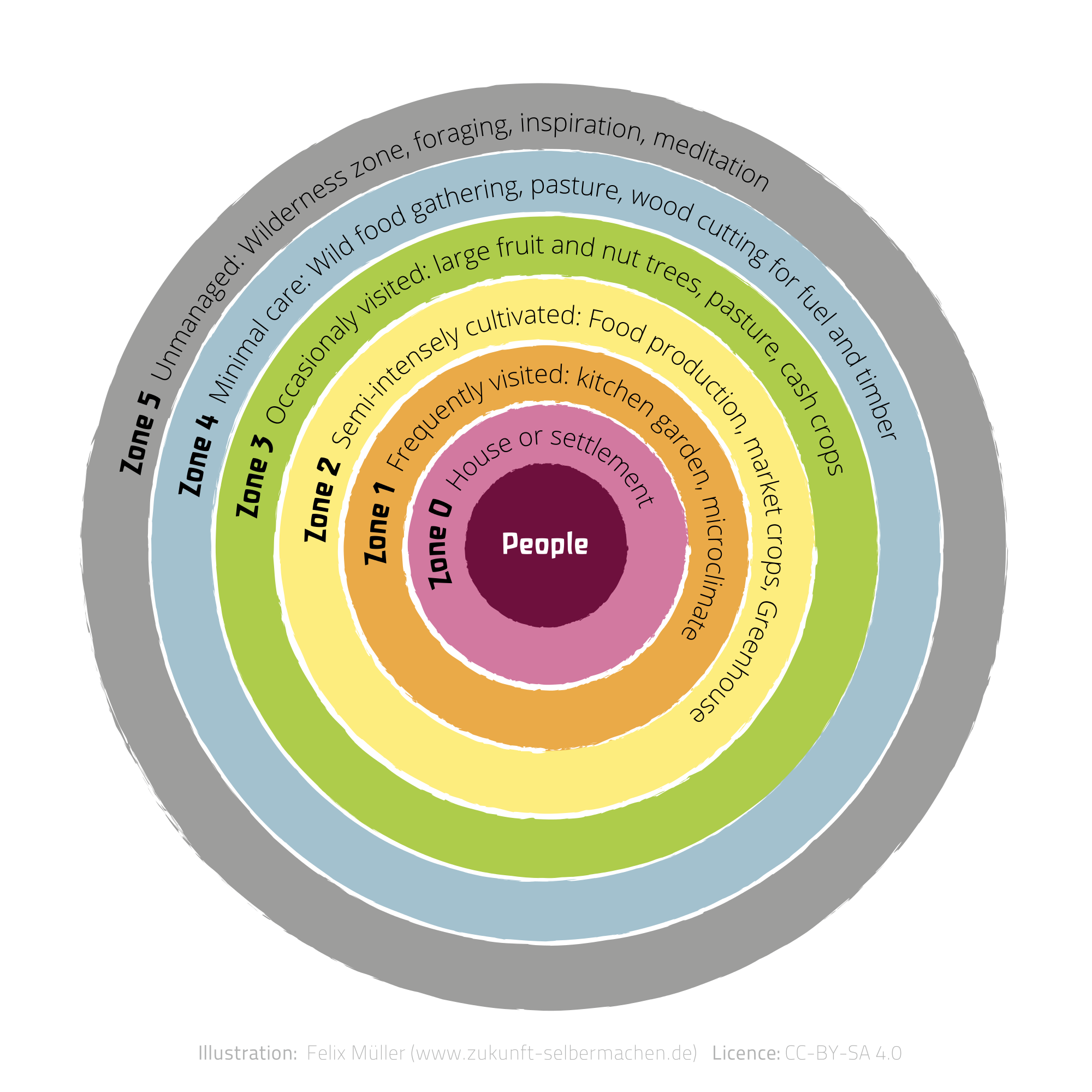

Permaculture zones or rings (Courtesy of Felix Muller).

How is this possible? Arguably, by embracing the permaculture design for food production and development and planning. The design concept of permaculture rests on a series of concentric circles or rings. The human settlement occupies the center with different degrees of food production and nature occupying the successive rings. The outmost circle fully belongs to pristine wilderness. All rings are interconnected by pathways, allowing inner-city residents to escape to the woods for an afternoon or for farm laborers to enjoy an exhibit at an art museum.

Aside from the environmental benefits, permaculture presents communities with economic benefits. Local food production is a source of jobs. Permaculture avoids chemical fertilizers and pesticides and operates at a human scale. Such work requires many hands and many skills. For instance, a majority of landfill wastes consists of food scraps. This could be turned into compost, returned to the soil, and close the waste loop. Handling, managing, and converting such waste into the super-food of plants requires workers, both blue-collar and white-collar. Faust cited Calcutta, India, where over 22,000 people work processing the city’s compost. Struggling localities in America might look to permaculture as a way to improve the health of their residents, offer them a purposeful livelihood, and serve as incubators for their economy.

If you’re interested in permaculture, Andrew Faust will be returning to the Brainery on Friday May 13, 2016 at 6:00 p.m.

The Brooklyn Brainery, 190 Underhill Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11238, www.brooklynbrainery.com

[…] Source: My Introduction to Permaculture | Another Town on the Hudson […]

Thanks for the repost! Can’t wait to hear what your readers think.